Common Name: Jelly Fungus – The gelatinous texture of the fruiting body gives rise to the general jelly description which implies being soft but resiliently firm, partially transparent, and semisolid. While the jelly appearance is true of many of the species, it is a widely inclusive designation. Brain-like, scattered blobs, and shaped like a leaf or an ear are descriptions that would better describe individual species. The species above is commonly called Jelly Leaf, or, alternatively, Brown Witch’s Butter as an example of confusing fungal terminology.

Scientific Name: Tremellales, Dacrymycetales, Auriculariales and Sebacinales are the four Orders into which jelly fungi have been taxonomically assigned for now. The Latin word for tremble is tremulus giving rise the trembling order. Dacry is Latin for tears, implying wetness. Auricula is Latin for ear, here used for the shape of the fungus. Sebaceus is Latin for tallow which would imply a fatty appearance. The jelly fungus above is Tremella foliacea, which translates from Latin to something that approximates “tremulous leaf.”

Potpourri: Jelly fungi, while of marginal importance to the ecological network of the forest, attract the inordinate attention of hikers passing through. They come in a variety of colors, striking many as an unlikely yet obvious protuberance on fallen logs. The key attraction is the gelatinous texture of the overlapping random lobes and curls, suggestive of an underlying reason for their topology. And there is one. Like all fungi, they are the fruiting bodies of the fungal mycelium that is embedded in the rotted wood (and in some cases on the backs of other, parasitized, fungi) on which they appear. The only function of the jellied fruiting bodies is to provide an effective means to launch as many of their reproductive spores into the air to propagate the species.

The taxonomy or scientific classification of those species of fungi that are jelly-like in appearance has not yet been settled conclusively. The DNA research necessary to establish phylogenic assignations has understandably been sparse due to both the obscurity and relative insignificance of lumps of colored jelly. For this reason, they are almost always combined in field guides as a single category entitled jelly fungi since they are visually distinctive.[1] However, there are some details that are germane. Jelly fungi are all in the largest class of fungi that includes the well-known gilled mushrooms named Basidiomycota, named for the basidia, the structures on which the reproductive spores are produced. Jelly fungi have at least one physiological features that distinguish them within the larger class. Along with rusts and smuts, they have basidia that are divided into sections by a cellular wall. They are therefore called septate or divided basidia basidiomycetes and are grouped in the subclass Heterobasidiomycetes (this was at one point established as a class named Phragmobasidiomycota along the endless timeline of sorting out fungal genetics). [2] The idea is that they are different (hetero) from the rest of the class that are, not surprisingly, called Homobasidiomycetes.

While the esoterica of fungal taxonomy establishes the credentials of biological determinism, it hardly satisfies the practitioner. After all, Carl Linnaeus created “the road map of biology” four centuries ago based entirely on physical appearance. The fungal details were expanded some years later by another Swede named Elias Magnus Fries and acclaimed as “the Linnaeus of Fungi”. Reproduction is what creates and perpetuates living things so taxonomy focuses on the details of its execution. For fungi, it is all about how and where the spores are created. The evolution of fungi over time or phylogeny is then at least in part about better ways to form and release spores into the environment. From the phylogenic perspective, jelly fungi constitute an early experiment with spore dispersal that gave way over time to the evolution of mushroom shaped structures with gills and pores as improvements. The mushroom shape of many fungi that succeeded the jellies improves on the crucial propagative function with basidia extending outward from the sides of gills or pores for better dispersal. While the jellies survived, mushrooms thrived. [3]

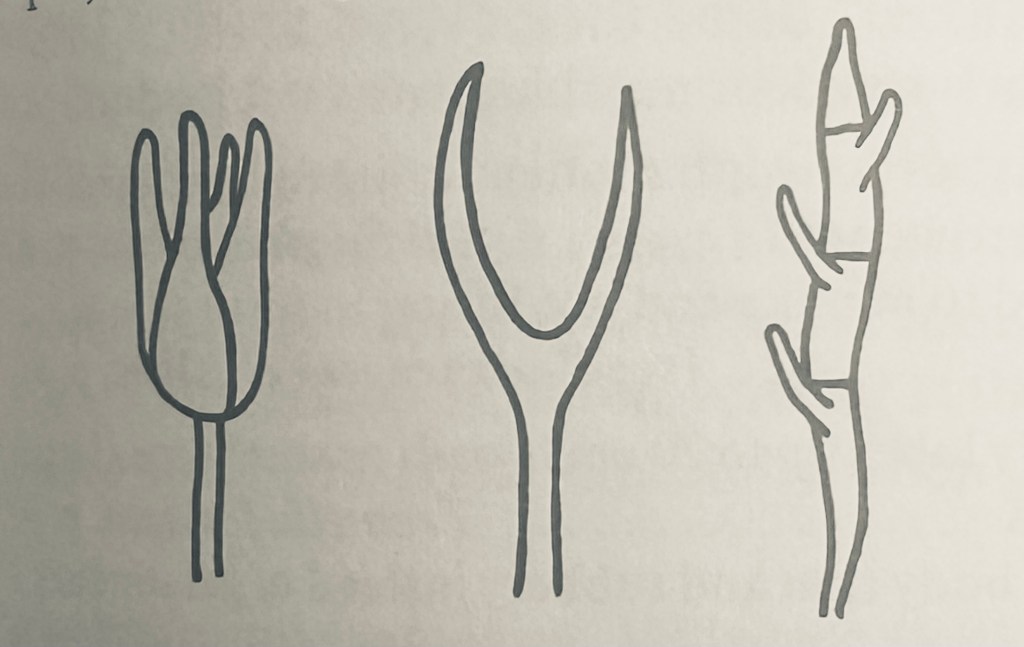

While speculative, it is plausible that the jelly-like structure evolved in an area or region with intermittent and restricted rainfall, as it desiccates when dry and revives on the restoration of moisture. This would provide for the release of spores only after a rain to better promote spore dispersal and germination. Most if not all fungi have a method to control the release of spores to coincide with the favorable environmental conditions of moisture. The different shapes of the basidia in the various orders of jelly fungi all serve to extend the spore formation and dispersal structure, the basidia, through the jelly to reach open air for wind dispersal. It is probable that the different shapes of the basidia were due to the classic Darwinian process of random mutation producing variants that on some relatively rare occasions, led to an improvement in the overall population of the new genetic code map. The longitudinally septate basidium on the left defines the order Tremellales, the forked shape in the middle is Dacrymycetales, and the transversely septate arrangement is Auriculariales. [4]

The edibility of jelly fungi has long been a matter of conjecture. While jelly implies edible and no jelly fungi are known to be poisonous, there is scant evidence one way or the other. This is certainly in part due to their slimy texture that would more likely repel than attract the fungivore. One field guide distinguishes those jelly fungi listed as either inedible or nonpoisonous. [5] It is not clear what criterion might have been used to establish the distinction. There is one jelly fungus that is universally recognized as edible. Auricularia auricula (literally ear-ear in Latin) commonly called wood ear, tree ear, or Judas’ ear, is common globally across the northern hemisphere. It is the earliest known fungus to have been grown commercially, dating from 600 AD in China where it is known as Mu Ehr. In 1997, it was the fourth most important edible mushroom in the world. [6] It is still at the forefront of cultivated edible fungi.

Witch’s Butter (Tremella mesenterica) is second only to tree ear among known and recognized jelly fungi. Both the common name and the scientific name exemplify the fanciful names assigned by both custom and intention. Since it is yellow, the butter aspect is unremarkable, but since it is found randomly growing in dense woods, ascribing it to the dark and usually evil connivances of witches is metaphorical. The species name mesenterica translates as middle intestine, which, while descriptive, connotes for most people an aversion to any consideration of edibility. The supernatural association is enhanced by the physical nature of the fungus, which will desiccate to become indistinguishable only to come coursing back to full prominence when moistened, or perhaps by some incantation. [7]

Dead Man’s Rubber Glove (Tremella reticulata) is another of the jelly fungi with a common name that overemphasizes a descriptive mnemonic at the expense of any consideration as an edible. It is also called White Coral Jelly due to its similarity in basic structure to the coral fungi characterized by upright, branched lobes. In both cases (jelly and coral), branching and widening produces more surface area over which to distribute the spore forming hymenium. As an example of the nomenclature variability among jelly fungi, Jellied False Coral, almost identical in appearance to the others, is listed in a more recent field guide as Tremellodendron schweinitzii. This same reference lists T. reticulata as Sebacina sparassoidea in pointing out that species of the Tremella genus are parasitic on other fungi, mostly those of the genus Stereum, whereas T. schweinitzii is mycorrhizal. [8] The study of jelly fungi continues as details of its taxonomy are revealed.[9]

The most stygian of all the jelly fungi is Exidia glandulosa, commonly called Black Jelly Roll. Not surprisingly they are also called Black Witch’s Butter, or, in the UK, simply Witch’s Butter, with the presumption that any butter from witches would be black. E. glandulosa is closely related to the edible tree ear which raises the inevitable edibility question among those who fancy fungi (second only to the “is it poisonous?” question). Those field guides that include it are either silent on the subject (assuming no one would want to know), or pointedly facetious in noting that its edibility is “unknown, and like most of us, likely to remain so”. [10]

Or perhaps we should give jelly fungi another look as a culinary choice. Providing nutritious food to the burgeoning human population is one of the challenges of the current century. Tree ear (A. auricula) has been systematically analyzed as the only jelly fungus that is currently cultivated and consumed and found to be highly nutritious. One hundred grams of dried tree ear consists of over four grams of protein and almost twenty grams of fiber with 351 calories of energy. [11] It has been suggested, albeit by a decidedly outré American mycologist, that “old tradition, in many countries, attests that the Tremellas are Fairy bread” and that “pretty indeed must have been the feasts when piles of such purity filled the board.” Noting that some jelly fungi are “delicious when slowly stewed,” and that others are “gelatinous, tender – like calf’s head,” it is held that all fungi, save the poisonous Amanitas, deserve a taste. [12] There is a lot to learn about the Kingdom Fungi, as it takes its rightful biological place beside plants and animals, maybe even food for thought.

References:

1. Lincoff, G. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mushrooms, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1981. pp 379-386.

2. Kendrick, B. The Fifth Kingdom, Third Edition, Focus Publishing, R. Pullins Company, Newburyport, Massachusetts, 2000, pp 82-83, 102-103.

3. Stevenson, S. The Kingdom Fungi, Timber Press, Portland, Oregon, 2010. pp 100-127.

4. Arora D. Mushrooms Demystified, Second Edition, Ten Speed Press, Berkeley, California, 1986. pp 669-675.

5. Miller, O. and Miller H. North American Mushrooms, A Field Guide to Edible and Inedible Fungi, Morris Book Publishing, Guilford, Connecticut, 2010, pp 491-498.

6. Chang, S. and Miles, P. Mushrooms, Cultivation, Nutritional Value, Medicinal Effect, and Environmental Impact, Second Edition, CRC Press, New York, 2004, p 206.

7. Roody, W. Mushrooms of West Virginia and the Central Appalachians, The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, 2003, pp. 452-455.

8. Baroni, T. Mushrooms of the Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada, Timber Press, Portland Oregon, 2017 pp 510-519.

9. Hyde, K. et al. “Towards an integrated phylogenetic classification of the Tremellomycetes” Mycosphere. 8 January 2016 Volume 15 Number 1 pp 5146–6239.

10 Arora D. op cit. p 673.

11. Chang, S. and Miles, P. op cit. p 29.

12. McIlvane, C. and Macadam, R. One Thousand American Fungi, General Publishing Company, Toronto, Canada, 1973, pp 526-531